For several years now strategists and geopolitical analysts have been talking about the changing global order. But events over the past one month have accelerated this discussion, with global investors selling U.S. equity, bonds, and the greenback. As of the time of writing (April 22, 2025), international equity – proxied by MSCI EAFE – has outperformed the S&P 500 by 22% YTD in U.S. dollar terms, while emerging market equity has also beat its U.S. counterpart by 13.5%.

The shift in narrative from “U.S. exceptionalism” at the end of last year to “U.S. recession” today has also been rapid as the S&P 500 fell 20% and bounced strongly after as the U.S. administration climbdown on its tariffs threat. Stock-to-bond ratio has fallen back to the trend post-pandemic trend while Mag-7 now look relatively cheap at 24.6x forward earnings – last seen at the depth of the 2022 bear market (Figure 1). Mag-7 stocks are now trading at “only” 25% valuation premium relative to the S&P 500 (currently at 19.6x), the lowest ever.

As uncertainty remains high and VIX stays elevated, investors might wonder whether this is the end of U.S. hegemony or simply a reversion to the mean for U.S. economy and assets, which have trounced the rest of the world following the pandemic.

Structurally, the rise of China and India have put a question mark on whether U.S. role in global institutions such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, NATO, and World Trade Organization will be eroded over time. And as emerging economies account for an increasing share of global GDP, their governments have been pushing for larger role and voting share in international institutions that help shape the global order in their favour.

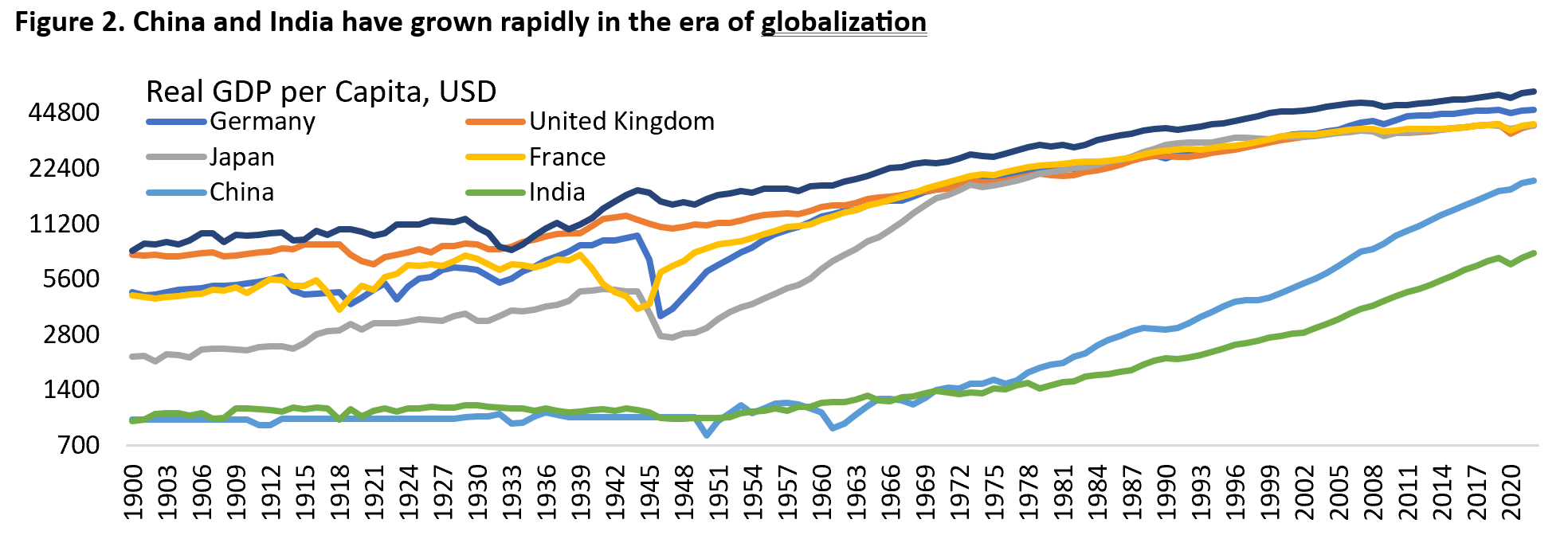

Over the past three decades, multi-lateral trade framework and globalization have allowed countries such as China and India to become an emerging “superpower” and many emerging countries have seen rapid growth thanks to foreign direct investment (Figure 2). A changing global trade rule based on multi-lateral framework to a bilateral approach would make it more difficult for countries across Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America to grow faster by orienting their industries to cater demand from rich, developed one.

For the median U.S. voters, however, the pendulum swing towards nationalistic sentiment and warm welcome for populist candidate is perhaps only logical given their living standards have stagnated even as poorer countries are becoming richer. Goods exports have been increasingly dominated by emerging countries, and exports by U.S. and other advanced countries have barely grown in the past two decades. Rising inequality and declining labour share of income have also boosted the popularity of far-right and far-left parties across developed countries (Figure 3).

It’s unsurprising then, that voters blame globalization as the cause of their suffering and perceived decline in living quality. Most young people in the developed countries are now behind their parent’s generation in terms of owning a house and the ability to progress higher in their career. Meanwhile, higher education is becoming more expensive and yielding lower return on investment – contributing to the burgeoning student debt liability for many Americans.

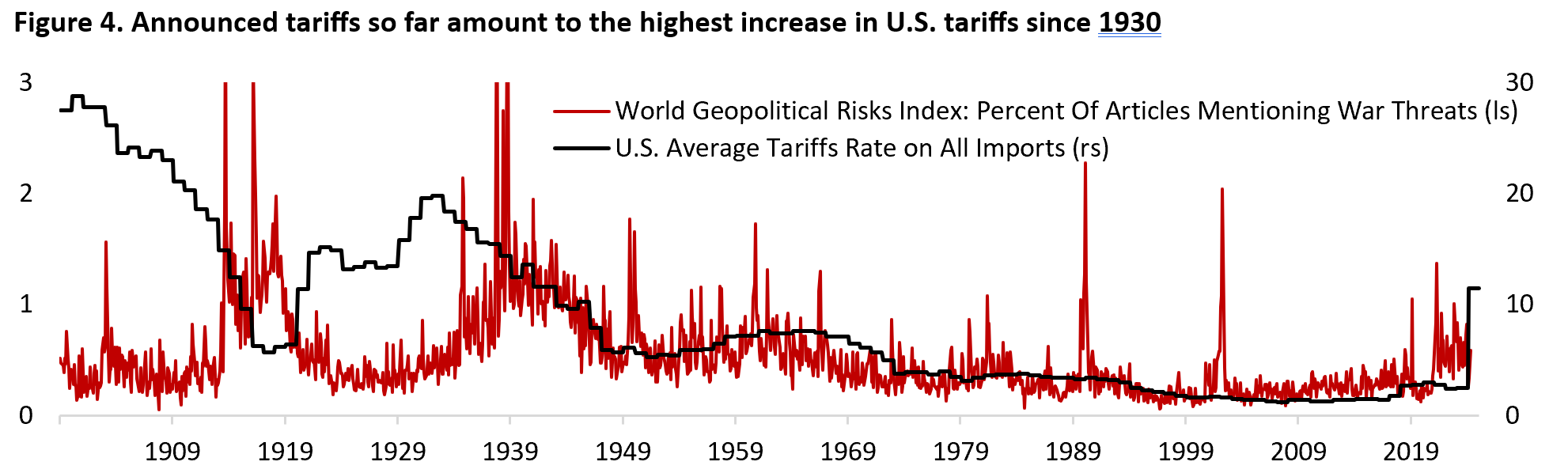

The worry for many developing countries today is the potential decoupling of the first and second largest global economy, even as U.S.-China tariffs are likely to be negotiated lower. All the announced tariffs so far amount to the largest increase in U.S. tariffs since President Herbert Hoover enacted the Smoot-Hawley tariff act in June 1930 with the initial goal of increasing protection for U.S. farmers who were struggling to compete with imports from Europe, before expanding to other industries (Figure 4). Other countries retaliated and global trade slumped as much as 66% between 1929 and 1934. As this happened following the World War I, countries that previously relied on boosting their exports to pay for the war reparation to the U.S. and other victorious nations were soon enough finding it difficult to meet their obligations. This translated to a deep discontent for many countries, including Germany, which further raise the nationalistic fervor in the years that follow up to the beginning of World War II. The longer tariffs are implemented, the larger the damage will be to the U.S. and global economy. For equity investors, overweigh defensives, large-cap and quality factor should help weather the turbulence.

The bottom line is that a prolonged tariff would ultimately send the U.S. economy into a recession, translating to a much higher unemployment rate and lower growth. Given that inflation and the economy are among the top concerns of American (and the current tariffs are good for neither), this could translate to the Republicans losing their seats in the mid-term election.

It is increasingly likely that the announced tariffs will be negotiated lower, as U.S. Treasury Secretary Bessent hinted tariffs on China could be cut by half. The situation is highly fluid with President Trump is opening the room for bilateral negotiations and many countries now incentivized to reduce their trade deficit with the U.S. by buying more from the U.S. producers. During President Trump’s first administration China agreed to buy US$ 200 billion of U.S. goods over two years, although this was disrupted by the pandemic and never fulfilled. European countries could also buy more of U.S. natural gas or threaten to impose levies on US digital companies if negotiations fail. This would expand the transatlantic trade war to the service sector through the potential tax on digital advertising revenues – hitting tech groups such as Meta and Google.

Perhaps more directly felt than the impact of tariff itself is the effect that elevated uncertainty creates. Coincident indicators show that U.S. economy is currently running around trend, but the trajectory across various indicators are deteriorating (Figure 5).

Barring a climbdown on tariffs from President Trump’s administration, goods manufacturers in the U.S. will face a tough rest of the year as demand destruction from higher prices materializes. This could translate to a significant headwind for profit margin across industries, especially in the import-heavy industrial and consumer discretionary sector. Despite the intention to bring manufacturing base to the U.S., President Trump’s tariffs have in fact make it more expensive to build and operate a manufacturing base in U.S. amid higher import cost of raw materials and unfinished goods.

Second, consumers are pulling back on spending and boost their savings as the outlook for their income growth and employment deteriorates. Over the past two years U.S. consumer spending has been increasingly driven by the top 20th percentile of households (Figure 7). A negative wealth effect from declining equity prices could translate to a pullback for spending especially on discretionary items. Worryingly, credit delinquencies are also increasing with credit card default rate at the highest since global financial crisis (Figure 8). Low and middle-income households have been suffering, with consumer spending increasingly dominated by the high-income households. Negative wealth effect from the decline in equity and house prices could accelerate the slowdown in consumer expenditure going forward.

The good news is that U.S. private sector layoff has remained relatively muted despite the uncertain demand outlook as highlighted by initial and continuing jobless claims still below pre-pandemic averages. Most of the recent layoff announcement in the U.S. has been dominated by the federal government amid DOGE efforts to reduce government spending. The worry is that deteriorating backdrop of global growth will lead companies to start laying off their workers (Figure 9). Given the already normalized U.S. consumer spending and the labour market, further softening on either front will not be welcome by the Fed and risk assets as it implies real GDP growth running below potential. Job openings have fallen close to pre-pandemic level and quit rate has fallen even further to below 2018 level. The Atlanta Fed wage growth tracker showing the premium for moving jobs vs staying have largely diminished, reinforcing the view of weaker bargaining power of workers today. Lastly, fiscal policy through lower government spending could also translate to a domino effect for the private sector, further tipping the balance for U.S. growth into a recession.

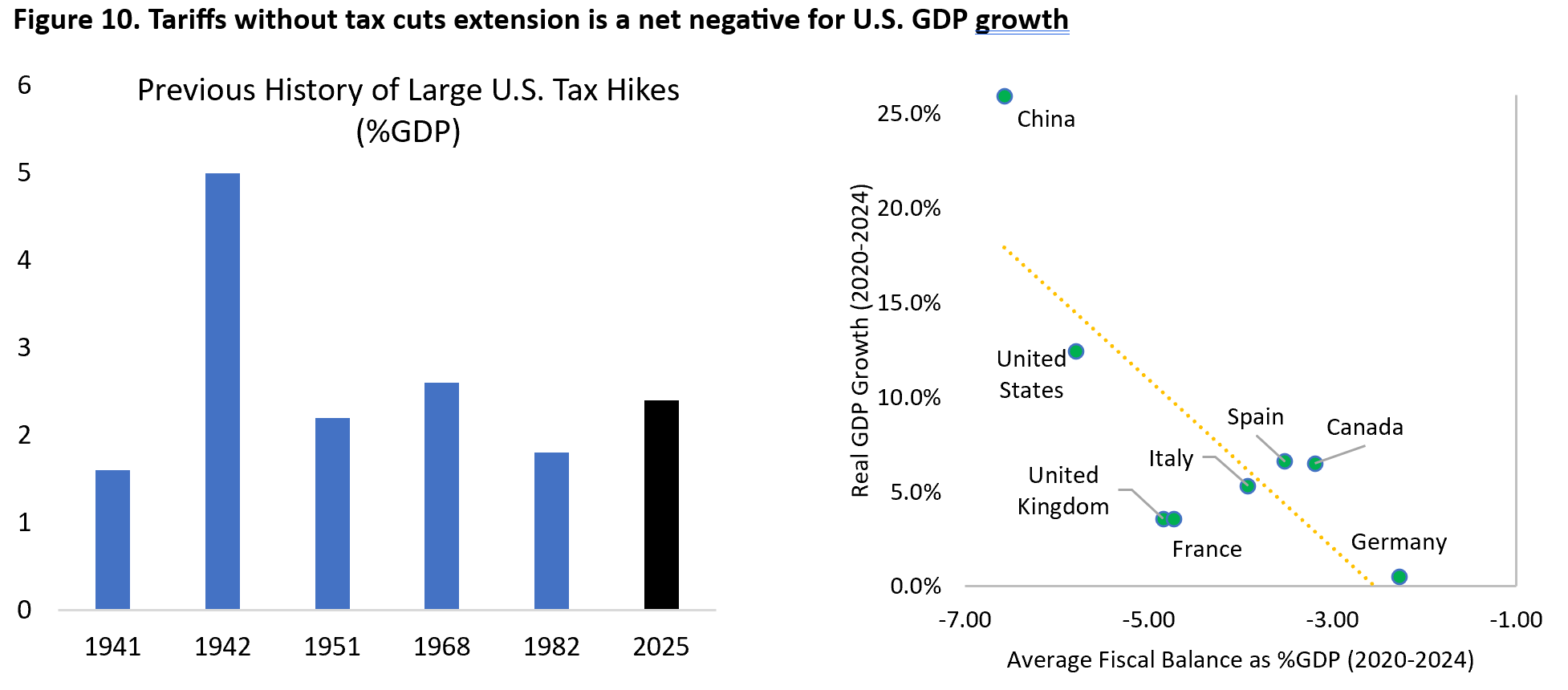

This all make fiscal policy the most important variable to watch going forward. The announced reciprocal tariffs amount to ~2% of GDP tax increase for the U.S. economy, which is a direct headwind for U.S. real GDP growth (Figure 10a). This is partially the reason why the dollar index fell following the announcement as investors were marking U.S. economic growth lower. U.S. consumer spending will be directly hit by the increase in goods import prices, and this price pressure will be felt disproportionately among low and middle-income households given the regressive nature of tariffs.

With the U.S. economy having enjoyed the fastest growth compared to other Western developed economies post-pandemic thanks to the generous U.S. fiscal thrust, a reversal of this could diminish the attractiveness of U.S. equities, especially as the rest of the world is stimulating through fiscal and monetary policy (figure 10b). President Trump has been trying to bring forward the planned tax cuts plan to the second half this year to offset the growth headwinds from tariffs.

Meanwhile, as the impacts of tariffs are expected to hit global growth and monetary policy is reaching their limit, governments around the world set to increase their fiscal deficit. Germany last month has already announced round of policy stimulus in the form of defense and infrastructure spending that is expected to be a structural tailwind for the Euro Area in the coming decade. This is the reason capital flow to European assets has been improving this year as the region’s outlook improves. Canada and China will likely also announce similar measures in the coming months.

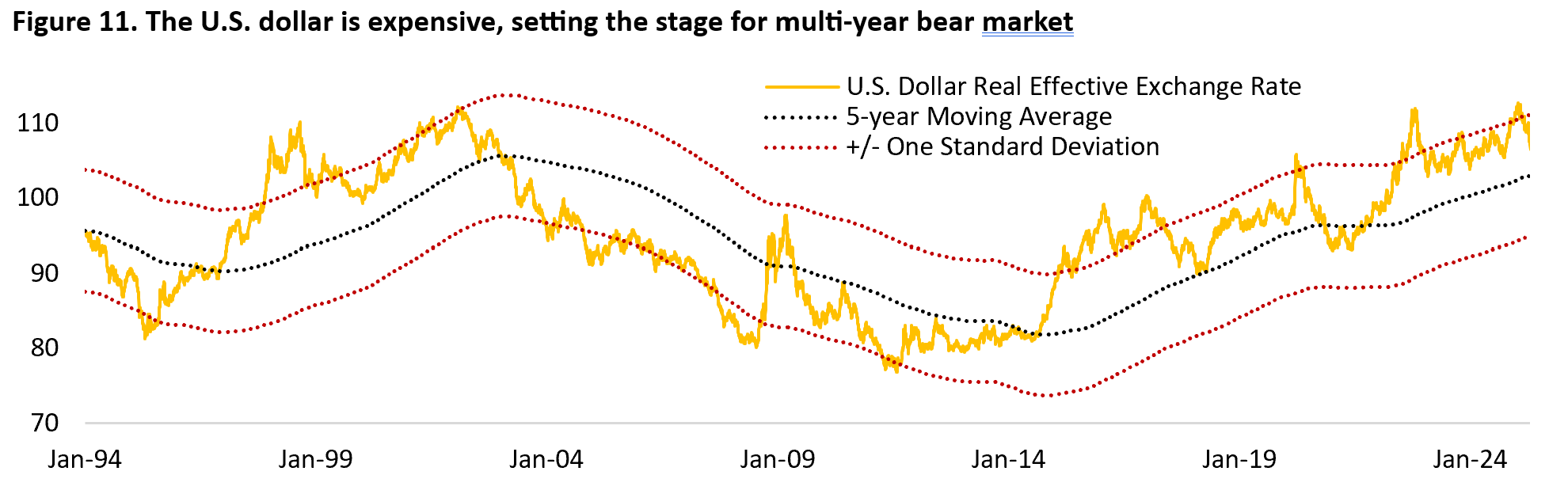

In a multipolar world, China and other emerging countries will try to build trade and financial network that is less U.S.-centric. We have seen this in motion with trading blocs such as Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which includes major developed and emerging countries but excluded the U.S. Over the longer run, tighter trade and economic relationship between countries and regions outside U.S. means central banks will diversify away from U.S. dollar and Treasuries in their foreign currency reserves. This could make it more expensive for the U.S. government to borrow through higher term premium and reduce the share of greenback in global trade invoicing. We called the top in U.S. dollar last year and believe there are few reasons why the U.S. dollar will continue to weaken in the coming years. First, the dollar is expensive and overvalued relative to its trading partner, even after adjusting for inflation (Figure 11). Second, lower trust on the U.S. financial system and rule of law should translate to diversification away from the greenback. Lastly, the likely peak of U.S. stock market share in global equity should also mean capital moving from U.S. assets to the rest of world. Long-term investors including pension funds and sovereign wealth funds will look to diversify their holdings, which could bode well for international and emerging market stocks as capital outflow from the U.S. shift to previously overlooked assets. Note that historically, the dollar has a 10 to 15 years of bull and bear cycles.

The downside risk for U.S. GDP growth means we remain constructive on U.S. Treasury bonds, although we acknowledged that investors would demand higher risk premium amid the elevated U.S. fiscal policy uncertainty. Our 10-year fair value model for U.S. government bond – based on terms of trade, DXY, WTI Oil Price, CPI Inflation, and copper-to-gold ratio – point to below 3% yield.

For equities, we hold our constructive take on European equities as U.S. stock valuation remain elevated even after the 7% YTD correction on the S&P 500 (as of April 24). Figure 13 shows that valuation across many sectors have fallen relative to at the beginning of the year but is far from cheap. The drove towards consumer staples sector is also likely overdone with valuation now at the 98th percentile. Investors will likely use this as source of funding to buy risk assets once sentiment improve. Within defensives, healthcare remains our top pick amid very attractive valuation and earnings recovery following two years of profit recession, and we are leaning toward slightly overweight position in utilities while underweighting real estate.

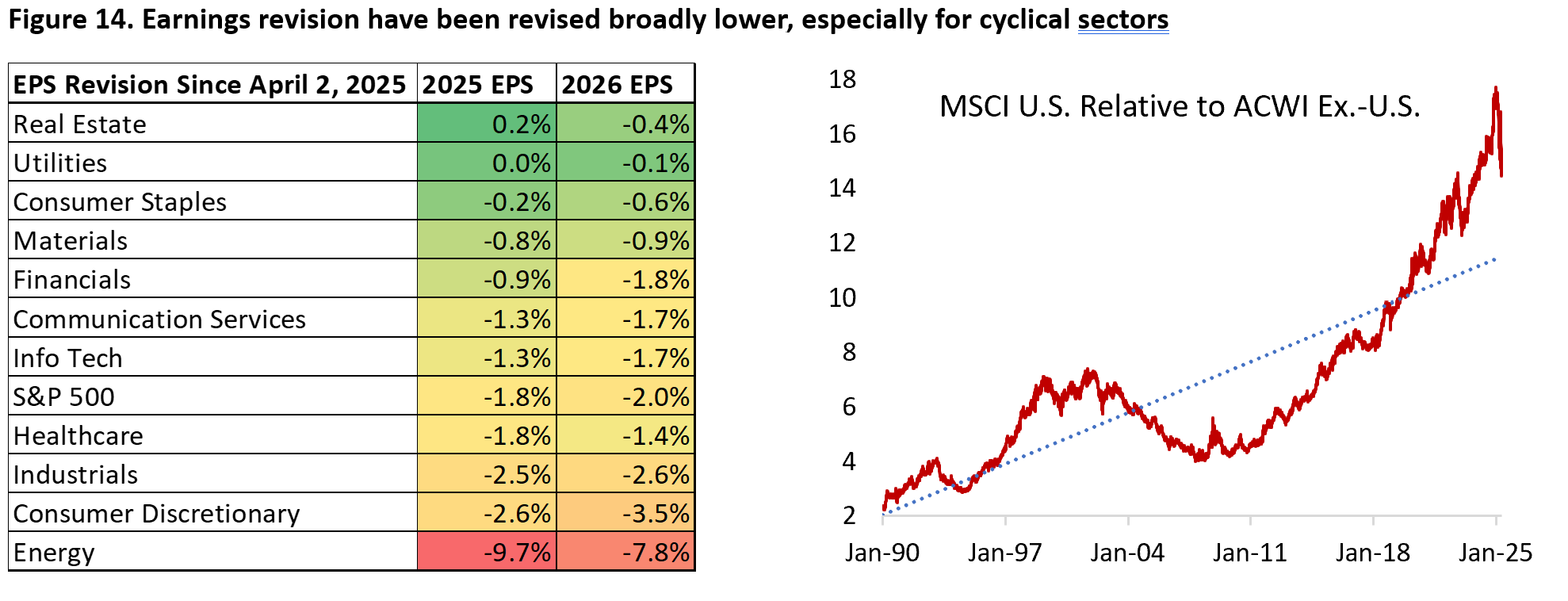

The outlook for consumer discretionary highly depends on whether tariffs will be negotiated, and this high uncertainty keep us from being more positive on the sector despite valuation having come down to a more reasonable level. Earnings revision could go even lower for consumer discretionary if the announced tariffs are indeed implemented with limited climbdown on the trade war (Figure 14). Overweighting cyclicals and underweighting growth sectors should have another leg.

Copyright © 2025, Putamen Capital. All rights reserved.

The information, recommendations, analysis and research materials presented in this document are provided for information purposes only and should not be considered or used as an offer or solicitation to sell or buy financial securities or other financial instruments or products, nor to constitute any advice or recommendation with respect to such securities, financial instruments or products. The text, images and other materials contained or displayed on any Putamen Capital products, services, reports, emails or website are proprietary to Putamen Capital and should not be circulated without the expressed authorization of Putamen Capital. Any use of graphs, text or other material from this report by the recipient must acknowledge Putamen Capital as the source and requires advance authorization. Putamen Capital relies on a variety of data providers for economic and financial market information. The data used in this publication may have been obtained from a variety of sources including Bloomberg, Macrobond, CEIC, Choice, MSCI, BofA Merrill Lynch and JP Morgan. The data used, or referred to, in this report are judged to be reliable, but Putamen Capital cannot be held responsible for the accuracy of data used herein.