“You can see the computer age everywhere, except in productivity statistics” – Robert Solow, 1987.

“Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure… Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!” – John Maynard Keynes, 1930, predicting that in hundred years people would work for only 15 hours a week.

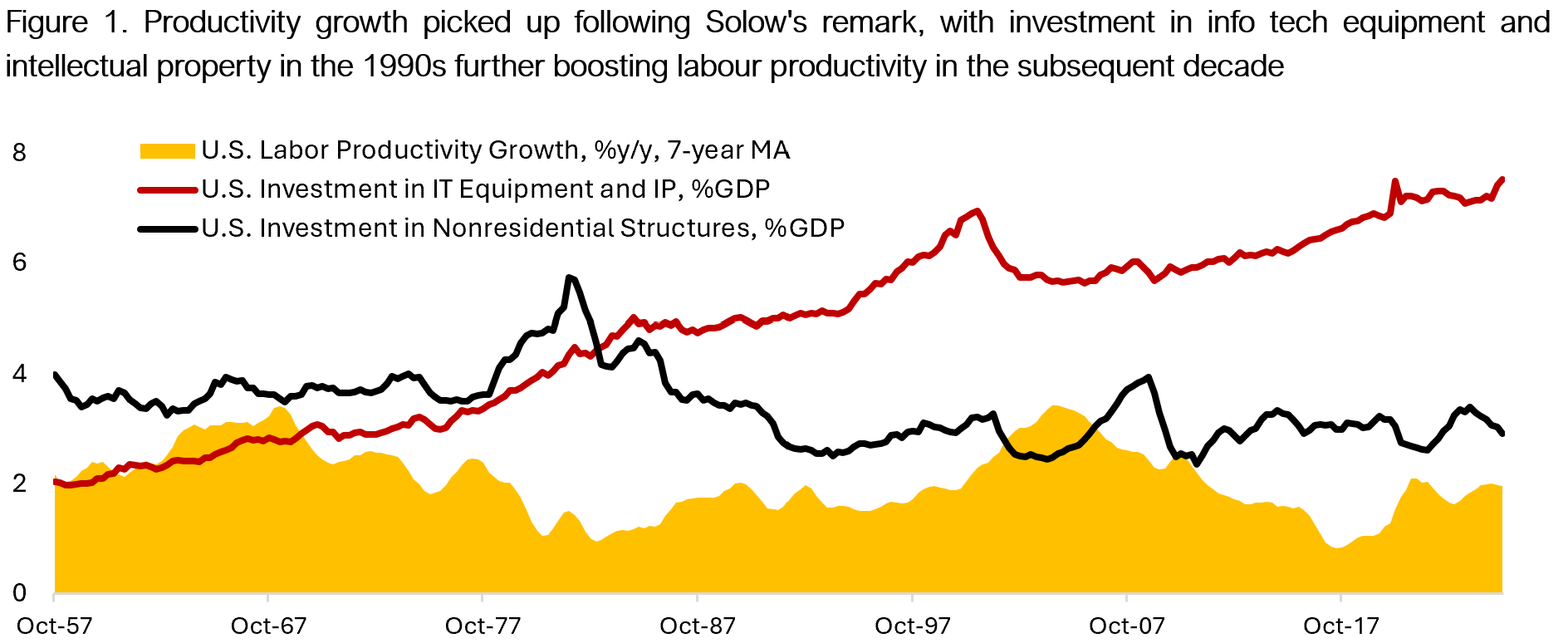

The first quote above, which later known as the Solow’s paradox, was first said in 1987 by Nobel Prize-winning American economists Robert Solow. Despite the third industrial revolution that began at the end of World War II with the invention and adoption of transistors, allowing digital transformation of previously analog formats – think of compact discs replacing vinyl records and cassette tapes – Solow observed that labour productivity growth has been weak. It was the early age of computer and the internet, with the first home computer introduced only 17 years earlier and only 15% of U.S. households estimated to own a computer. At the time, the U.S. economy had undergone a decade of boom in investment on technological equipment and digital infrastructure, which makes the weak labour productivity growth a curious phenomenon (Figure 1).

In hindsight, we know that Solow was simply too early in his observation. For technology to boost productivity, companies and individuals have to change and reorganize the way they work and do things which take time to do. Indeed, U.S. labour productivity growth accelerated in the decade following Solow’s remark.

Over the past forty years investments in IT hardware and software continue to structurally increase relative to the size of the economy, now accounting for 7.5% of U.S. GDP and significantly outpacing investments in non-housing infrastructures at 2.9% of GDP. The increasing investment in digital relative to physical infrastructure perhaps mirrors the shift in how we humans have increasingly spent more time in the virtual world such as social media, online gaming, and watching Netflix.

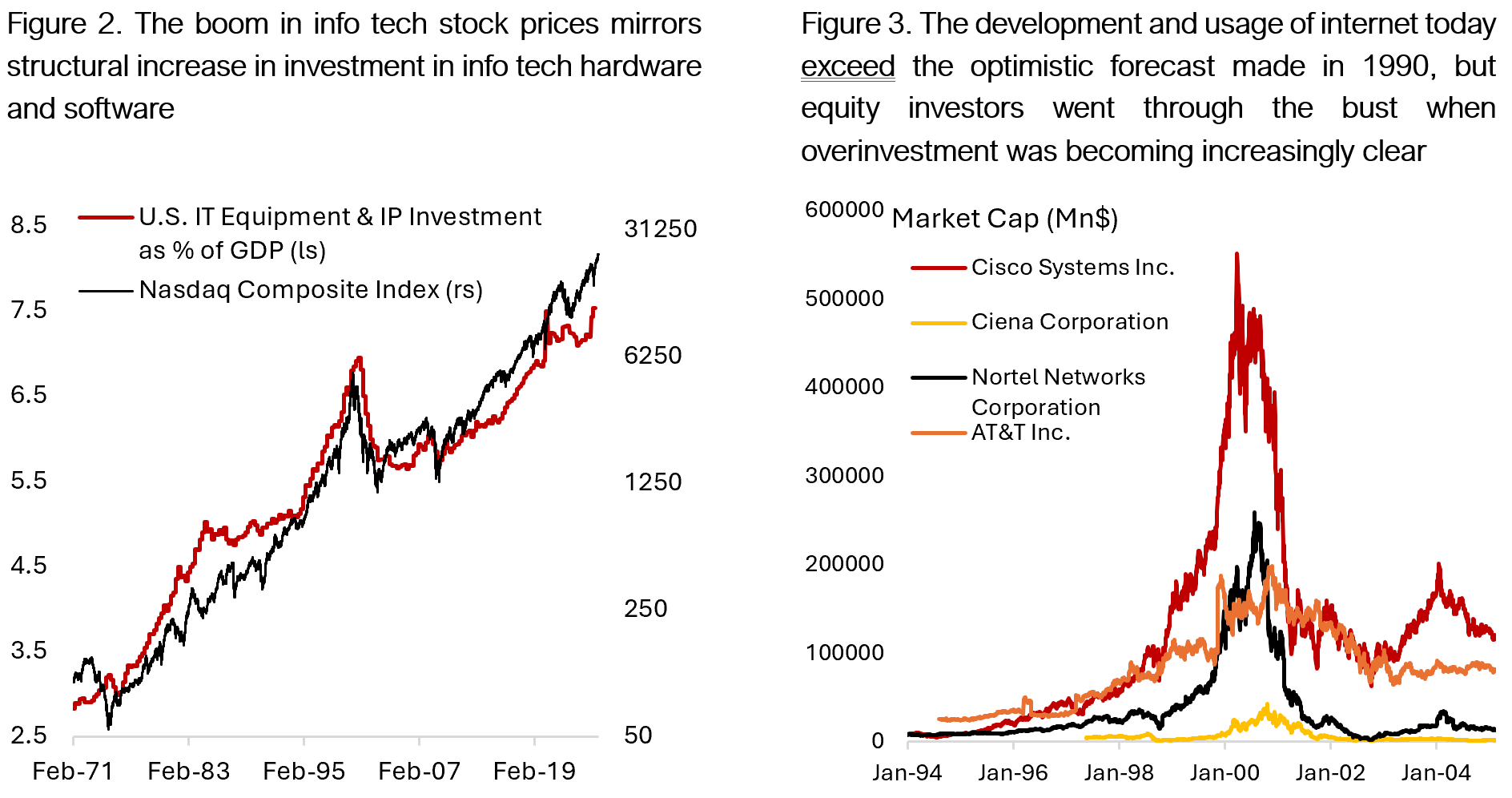

Some of us remember the boom-bust cycle in fiber optic investments between 1994 and 2002, which was part of the internet revolution and lay the groundwork for the digital world we have today (Figure 2). In this period, telco companies laid extensive networks of fiber optic cables amid the anticipation of exponential growth in internet traffic, leading to significant overcapacity. Telecom equipment providers such as Cisco, Ciena, and Nortel saw a boom in selling equipment to telecom companies that were aggressively building networks and laying fibers (Figure 3).

Although the internet bubble ended up in tears for many investors when the bubble burst in 2000 and 2001, the telco industry’s overinvestments in fiber optic cables significantly lower the cost internet connection for end users and allow internet platform companies, including Google and Amazon, to build on top of the available digital infrastructure. In the decade following the burst of internet bubble, labour productivity in the U.S. rose sharply as businesses and households saw an exponential increase in computer adoption and access to the internet.

Today, the big four chipmakers are the picks and shovels for the AI boom, analogous to telecom equipment providers for the internet thirty years ago. In the next phase of AI development, companies built on top of the current investment in data centers, training, and inference, will likely be the winners – not unlike the Netflix, Facebook, and Google of today. Whereas the first and second industrial revolutions boosted primarily the productivity of manufacturing workers, the ongoing AI revolution has the potential to boost productivity of workers in both good and service sectors. The music and movie industry are already seeing the disruptive impact of AI that compete with human talents. In science, AI has the potential to help formulate new drugs faster than previously possible and help radiologists to read scan results with greater accuracy.

With trillions of dollars being poured into investments in data centers and semiconductors, the relevant question today is whether we will see an overinvestment in AI training and inference capacity in the coming years. We don’t know for sure, but historically overbuilding may be a necessary evil or the cost of progress. In a tech conference in early October, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos argued that the huge surge of investment in AI is fueling a ‘good’ kind of bubble, delivering lasting benefits for society even if equity prices collapse as in the late 1990s – drawing the parallels with investment in fiber optic cable during the dotcom-era and the life-saving drugs that resulted from the 1990s biotech boom and bust.

The more immediate concerns for investors today surround the elevated expectation and valuation for many AI companies – in the latest funding round OpenAI is valued at US$500 billion, larger than the top three Canadian banks market cap combined, from $157 billion less than a year ago. In the first half of this year, OpenAI cash burn is estimated to be around US$2.5 billion on US$4.3 billion revenue. Thinking Machine Labs, co-founded by OpenAI’s former chief technology officer Mira Murati in February 2025, raised $US2 billion at a $US12 billion valuation with the focus to make AI systems more widely understood and customizable. The largest beneficiary on the investments in AI capacity has been Nvidia, who saw its revenue rise tenfold from $16 billion in 2021 to $165 billion over the last twelve months. Analysts expect revenue for the chipmaker to rise to $276 billion in 2027, and the stock is currently trading at 29 times its 2027 earnings estimate.

Another concern today relates to the sustainability of AI semiconductor investment. Nvidia’s recent $100 billion investment in OpenAI, who is also the largest buyer of its AI systems, evokes memory of the late 1990’s vendor financing practice to sustain growth. Then, telecom equipment providers borrowed heavily to help their telco customers finance the build-out of fiber optic cable. Currently, OpenAI commits to using 23 GW of new capacity, which would cost over $1 trillion to develop. To do so, OpenAI has raised $60 billion this year and is looking to lean on its partners’ balance sheet and the debt market.

But it’s also possible that we are underestimating the longer-term positive impact of AI. In fact, humans have in the past underestimate the pace of innovations and the associated rise in living standards. Figure 4 shows that prior to the start of the industrial revolution, GDP per capita was relatively stable. Only after the 18th century did living standards begin to accelerate with the invention of steam power. Perhaps among all the innovations in the past century, none is more important than those in the agricultural sector. Global food prices have declined and remained relatively stable over the past 50 years despite the doubling in world’s population (Figure 5). This refutes the fear of Chinese policymakers in 1979 that the country will at some point be unable to feed its population, which resulted in the disastrous one-child policy.

Although the focus on technological innovation in the past tended to be in the goods sector rather than services, there are many instances where the lower prices of goods translate to a lower service cost. Technological advancements are inherently deflationary. For instance, thanks to the investment in telecommunication infrastructure, the cost of a 3-minute phone call between NY and London has collapsed to essentially nothing in the past century, whereas the build-up in transportation industry resulted in the cost of passenger air transport and shipping to fall 90% and 78%, respectively, during the same period (Figure 6). Meanwhile, the dramatic decline in computing power has translated to the mass adoption of computers and brought down prices for services such as accounting (bookkeeping) and financial analysis, database management, and architectural design.

Given that technological progress tends to enrich the few inventors and capitalists with many losers in industries replaced by technology, however, technological breakthrough could translate to higher social tension in the period that follows. These tensions sometimes ended up in violence and had propagated ideas such as socialism and communism. Think of the textile workers who used to spin yarn and weave cloth in 1811 being replaced by the spinning jenny. In Nottingham, the replaced and suddenly unemployed weavers morphed into what later is known as the Luddite movement. They turned their animosity towards the machines and began destroying textile factories and the machinery. Little being thought at the time was that mass production of textiles means lower prices for consumers and eventually translates into a greater demand for clothes (Figure 7).

Certainly, AI could also have a disruptive impact on workers across industries. Early research on the productivity boost from AI applications so far has been encouraging. In the paper by Dell’Acqua et al (Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality), researchers concluded that workers who were assessed as having below-average performance saw 43% jump in performance scores by using AI compared to only 17% increase for workers assessed as having above-average performance. In sum, AI could help level the playing field for less-skilled workers.

It’s early days for AI, but early research shows significant variation in the adoption and utilization of AI across different industries. So far, white-collar workers in the info tech, finance, and businesses tend to see greater benefits of using AI in their daily work whereas blue-collar workers in the hospitality industry saw less benefit from AI utilization (Figure 8). But this may simply reflect the natural progression of AI applications, which started first from Search, then integrated into productivity tools such as Microsoft CoPilot, and platforms that help engineers code faster – all these are tools that help mainly white-collar workers to their job more efficiently. However, AI has potential to be disruptive for blue collar workers as well, with improvement in self-driving capability potentially upending the transport industry and smart robots that could perform complex tasks being deployed in medical and manufacturing industry.

More worrisome is the job prospect for younger folks who tend to perform entry-level tasks and are now competing with AI. Brynjolfsson, Chandar, and Chen (Canaries in the Coal Mine? Six Facts about the Recent Employment Effects of Artificial Intelligence) highlight that early-career workers in the most AI-exposed occupation saw 13% relative decline in employment compared to negligible change for workers in less exposed fields. Increasingly, governments are also seeing the importance of developing their own AI models for military applications such as intelligence gathering, surveillance, and cyber warfare. In short, there are endless potential applications for AI models that we have yet to uncover, but this does not mean investors should bet the ranch on semiconductor companies either, as an air pocket or signs of overinvestment in data center capacity could swing the market sentiment and valuation away from today’s very bullish starting point.

Navigating Through the AI Revolution for Equity Investors

Looking at the proliferation of large-scale AI models and the rally in semiconductor stocks, it looks like the bulls will be winning for the third consecutive years (Figure 9). Investments in AI infrastructure continue to grow with analysts increasing the capex for the big four hyperscalers by over 35% so far this year. In August, McKinsey released a forecast on data center investments and expect $6.7 trillion will be cumulatively deployed in building data center infrastructure through 2030, a sum equivalent to 23% of the current U.S. GDP. Within this forecast, around $3.5 trillion is expected to be spent on servers, which include graphics processing units (GPUs) and central processing units (CPUs) – benefitting Nvidia, Broadcom, AMD, and other semi names we all are familiar with today.

Given the cyclical nature of IT hardware investments analysts have been wary of the potential for air pocket for chips demand, but based on companies’ reporting in the most recent quarter there are no sign that we are going to see one anytime soon. And indeed, the macroeconomic and monetary policy backdrop have been supportive of the animal spirit in the market.

The backdrop of the Federal Reserve easing monetary policy and ongoing technology boom is analogous to the period between 1994 and 2001. Figure 10 shows the Fed Funds Target Rate against U.S. GDP growth and the S&P 500. Note that during both the 1995 and 1998 rate cut, the U.S. economy was in rude health and the Fed was more concerned on the potential negative blowback to U.S. economy from crisis in Latin America (Tequila Crisis 1994) and Asia (Asian Crisis 1998). The U.S. financial market did see a tightening liquidity as a result of the Russian sovereign crisis with the failure of Long-term Capital Management (LTCM) in September 1998. The Federal Reserve organized a bailout for the firm and eased liquidity, which further amplify the mania in technology stock price.

Today, the U.S. economy is also in relatively good shape despite the slowdown in job market and impact of tariffs. In addition, the Fed is expected to cut policy rate by another 100 bps by the end of 2026. All these are supportive for risk assets and households’ spending, especially considering the rise in wealth from rising equity and housing prices over the past five years. To us, it feels more like1998 rather than 1995 or 2001.

To gauge the durability of investment spending on AI, investors could scrutinize hyperscalers’ capex plan relative to their free cash flow, which in the past 2.5 years have been increasingly allocated to building AI infrastructure. Magnificent 7 companies’ capital spending is expected to grow 53% this year compared to last (Figure 11), and analyst forecast capex intensity to remain high in the coming two years. For shareholders, this means lower free cash flow that could be used for share buyback and dividends. Unlike in 2022 when Meta’s share price was sliding as investors perceived the company’s investment on metaverse as wasteful, however, investors today think that the build out of AI capacity will pay off down the road. Still, given the elevated concentration in the S&P 500 index – with top 10 names accounting for 40% of the index – investors should rethink their approach in allocating to U.S. stocks.

There are other ways to play the AI theme without directly investing in the chipmakers’ stock that have rallied hard in recent years. For instance, there is a jump in demand for electricity and commodities for the build out of data centers. In the U.S. alone, power demand from data centers is set to triple to 600 TWh by 2030 from around 200 TWh currently, bringing the ratio from 5% to 12% of all energy demand for the country. If realized, this will be the largest increase in U.S. energy demand since the introduction and mass adoption of air conditioning in the 1960s. Given the construction of small modular reactor or nuclear energy source will take longer time than those for data centers, likely natural gas will play a role as a bridging energy source.

Meanwhile, old-economy industries such as heavy machineries and base metal miners have also benefitted from the demand in resources for building data center and other AI infrastructures. The outlook for copper prices is attractive given supply growth will most likely underwhelm demand growth in the coming decade, which should push prices higher. Recent accident in Grasberg site in Indonesia owned by Freeport highlights the sensitivity of copper prices to supply disruption. This makes it important for investors to invest in the actual commodity alongside the miners’ stock.

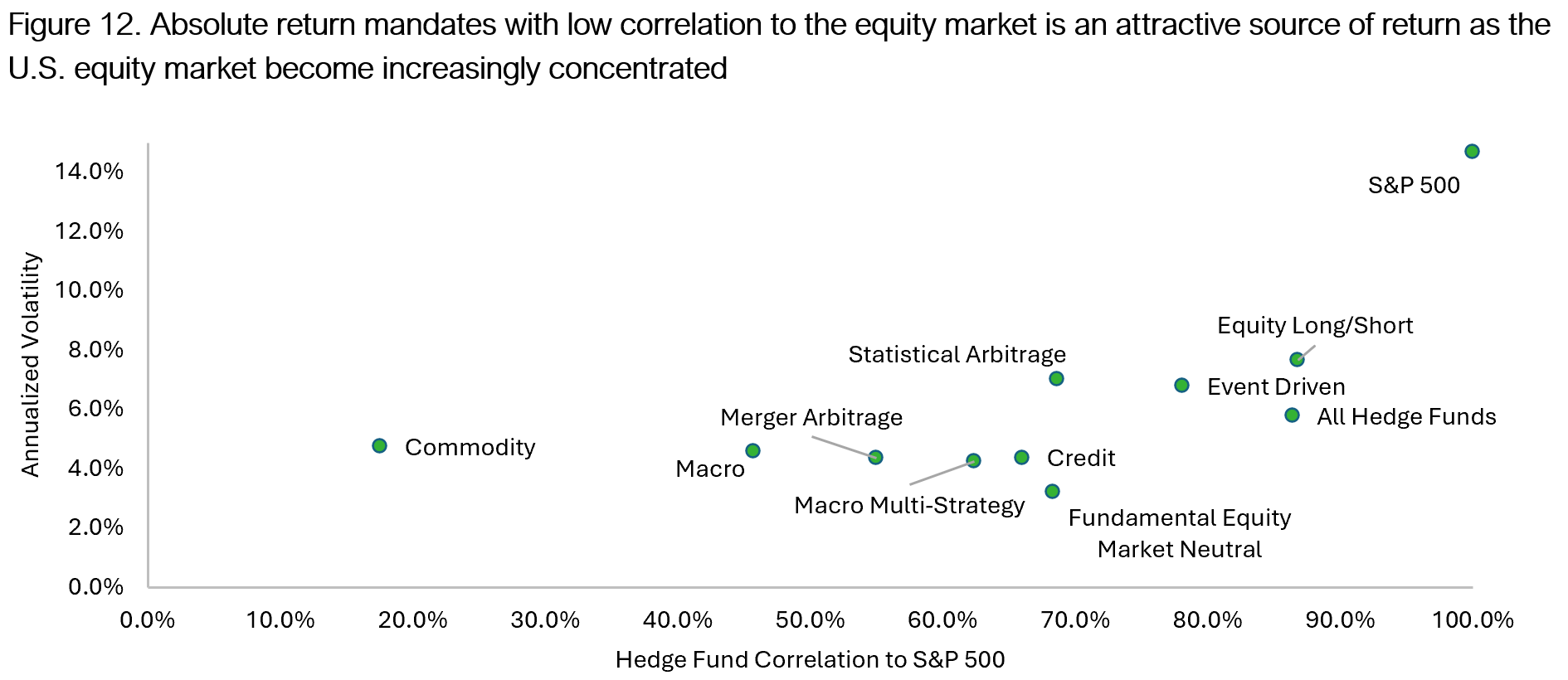

On top of diversification in the long-only equity portfolio, we believe having return sources that is not correlated to the broader market is also the key in navigating the current environment (Figure 12). Multi-strategy mandate with low correlation to the equity and bond market is perhaps the best diversifier, but having an equity market neutral or long/short exposure could also help reduce portfolio’s volatility and drawdown. We are not betting that the current AI boom will end soon, but diversification is becoming increasingly paramount in protecting capital.

Copyright © 2025, Putamen Capital. All rights reserved.

The information, recommendations, analysis and research materials presented in this document are provided for information purposes only and should not be considered or used as an offer or solicitation to sell or buy financial securities or other financial instruments or products, nor to constitute any advice or recommendation with respect to such securities, financial instruments or products. The text, images and other materials contained or displayed on any Putamen Capital products, services, reports, emails or website are proprietary to Putamen Capital and should not be circulated without the expressed authorization of Putamen Capital. Any use of graphs, text or other material from this report by the recipient must acknowledge Putamen Capital as the source and requires advance authorization. Putamen Capital relies on a variety of data providers for economic and financial market information. The data used in this publication may have been obtained from a variety of sources including Bloomberg, Macrobond, CEIC, Choice, MSCI, BofA Merrill Lynch and JP Morgan. The data used, or referred to, in this report are judged to be reliable, but Putamen Capital cannot be held responsible for the accuracy of data used herein.